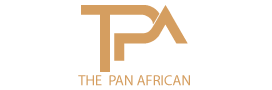

In the twilight of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta’s presidency, the formidable Police Commandant Mungai wielded immense power over the Rift Valley Province. Rumored to be related to Kenyatta and hailing from the same tribe, Mungai was a key player in the president’s inner circle. Meanwhile, Daniel Arap Moi, the Vice President, was seen as an outsider within this exclusively Kikuyu clique and endured frequent humiliation from Mungai and other high-ranking officials.

Moi’s plight is vividly depicted in Andrew Morton’s authorized biography, “Moi: The Making of An African Statesman.” One notable incident from 1975 describes Moi’s return from an OAU meeting in Kampala. Upon arrival, Mungai accused him of smuggling guns in a plot to overthrow Kenyatta. The commandant’s men conducted an invasive search at Moi’s Nakuru Oil and Flour Mills office, even subjecting the Vice President to a strip-search.

Morton recounts that Mungai’s contempt for Moi reached its highest when he slapped the Vice President twice in front of Kenyatta at State House Nakuru. Moi, in desperation, complained to Kenyatta, only to receive a rhetorical rebuke questioning his control over the police. Moi was left fearing for his life, praying nightly as he clung to his precarious position.

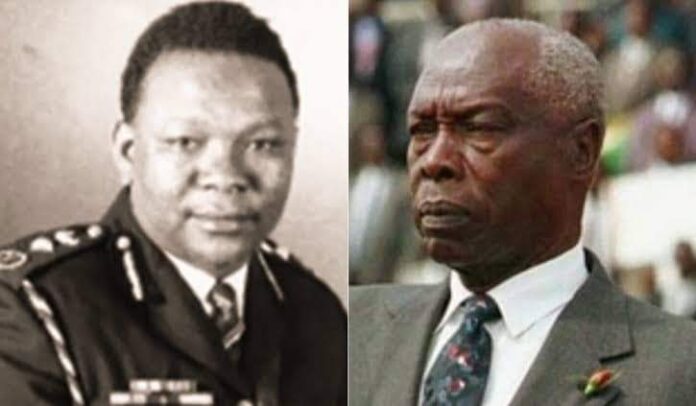

Kenyatta’s unexpected death before any constitutional amendments could be made catapulted Moi into power as the reluctant successor. Despite his ascension, he remained wary of the Kikuyu elite, confiding to Attorney-General Charles Njonjo his fears of assassination: “Hawa wa-Kikuyu wataniua” (these Kikuyus will kill me).

In a dramatic turn, Mungai fled from Nakuru to Lokitaung and then into exile in Sudan before settling in Switzerland. However, unable to bear the harsh winter, he wrote pleading letters to Moi, who surprisingly harbored no desire for vengeance. Mungai was allowed to return and retire peacefully.