Today, Nairobi is a bustling African metropolis — a city of skyscrapers, traffic jams, and endless ambition. But its birth wasn’t simply the result of the Uganda Railway chugging through the highlands in 1899. Long before steel tracks and colonial planners drew lines on maps, the land we now call Nairobi had a history, a name, and a life of its own.

The area was known to the Maasai as Enkare Nairobi, meaning “place of cool waters.” It referred to the Nairobi River and the lush swampland around it, a green belt teeming with wildlife. This was not the kind of place most people wanted to live — it was damp, mosquito-ridden, and prone to flooding. But for the Maasai and the Kikuyu, it was prime grazing and hunting ground. Maasai herders would seasonally move their cattle through, while Kikuyu farmers used nearby fertile soils to grow crops. It was a meeting point long before it became a city.

What many don’t realize is that Enkare Nairobi already had a role as a crossroads in regional trade. Long before the first railway sleepers were laid, ivory, livestock, and grains passed through the area on foot and by caravan. It was also a contested space — a borderland between Maasai grazing zones and Kikuyu farmlands, where occasional skirmishes broke out. This made it a place of both opportunity and tension, a natural frontier.

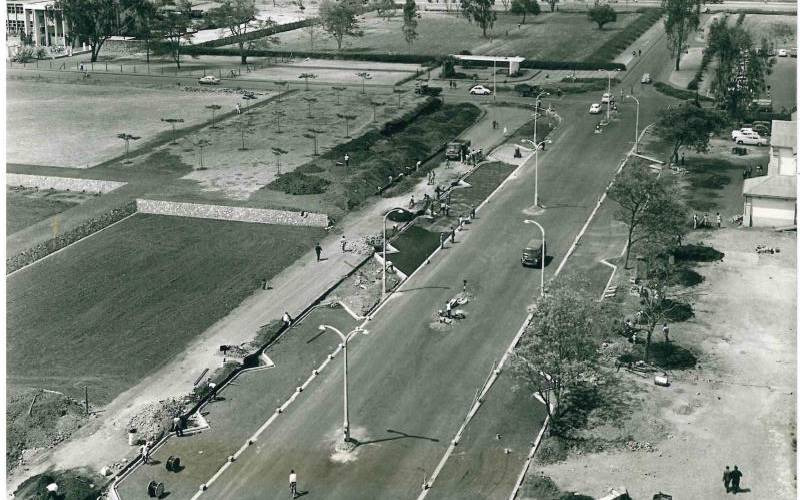

When the British began constructing the Uganda Railway in the late 1890s, they weren’t initially interested in founding a city here. They wanted a supply depot at a practical midpoint between Mombasa and Kisumu. Nairobi’s high elevation made it cooler than the coast, its flat terrain was ideal for building, and its proximity to water made it perfect for steam locomotives. But here’s the twist: the swampy soil nearly ruined their plans. Early railway workers complained that equipment would sink into the mud, and outbreaks of malaria sickened many. In fact, some British engineers argued for moving the base entirely.

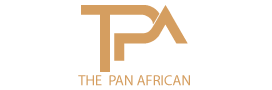

What changed the game was the arrival of traders and laborers — Indian railway workers, European settlers, Somali caravan leaders, and African porters — who began building a makeshift settlement around the depot. Shops, inns, and markets sprang up almost overnight. By the time the railway officially reached the site in 1899, Enkare Nairobi was no longer just a swamp; it was a hub of human activity.

One little-known fact is that the railway depot site was also chosen for its proximity to a Maasai cattle route. British administrators saw an opportunity to tax and control the movement of livestock, making Nairobi not just a transport hub but also an economic choke point. This early intertwining of transport, trade, and administration became the DNA of the city.

Within a few years, Nairobi became the capital of the British East Africa Protectorate, displacing Mombasa. The choice was as much about politics as practicality — Nairobi was inland, closer to settler farming zones, and easier to defend. But in those first years, the city was little more than a rough frontier town, a place of mud roads, timber buildings, and the constant mingling of cultures.

Nairobi’s origin story is often told as if the railway created it from nothing. In truth, it was born at the intersection of indigenous land use, trade routes, and colonial opportunism. The swamp became a city not because it was ideal, but because it was strategic — and like the cool waters it was named after, its history runs far deeper than the steel tracks that once defined it.