In the early decades of British colonial rule, Kenya was turned into a laboratory for some of the most controlling and racially discriminatory systems in Africa. Among them was the Kipande system, a policy that to many Africans felt like carrying around a shackle in their pocket. Though less famous than South Africa’s apartheid pass laws, the Kipande worked in much the same way—and in some respects, it was even more intrusive.

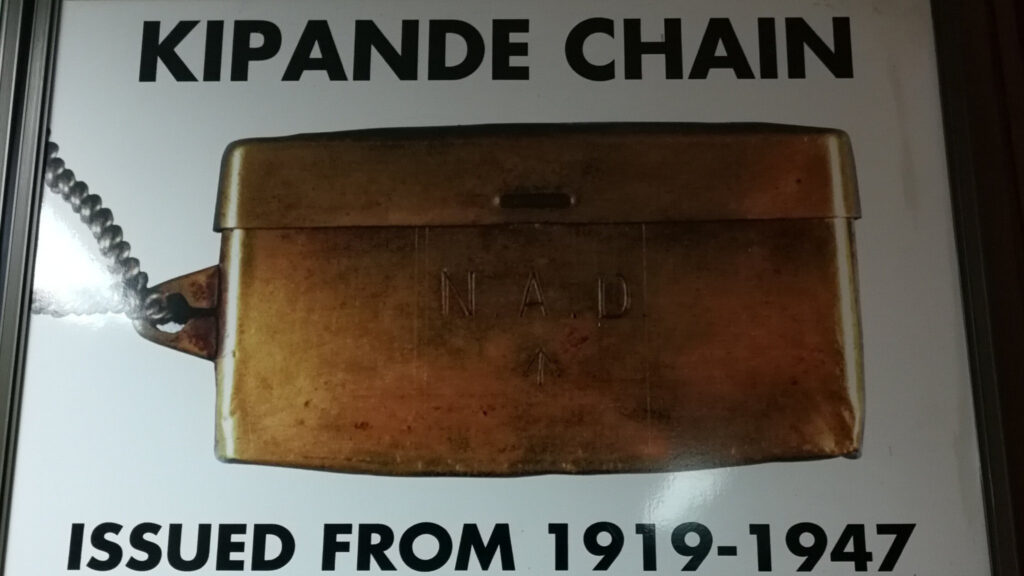

The word kipande means “piece” or “fragment” in Kiswahili, but for African men in colonial Kenya from 1920 onwards, it referred to a small metal container worn around the neck, containing an identity document. This card wasn’t just for identification—it was a tool of total control. The Kipande recorded the wearer’s fingerprints, work history, wages, and even comments from employers. It was the colonial government’s way of turning a person into a walking, trackable file.

Why the Kipande Was Introduced

The system came into force after World War I, when the British colonial government feared a shortage of cheap African labor for settler farms and public works. Many returning African soldiers had seen the world and were less willing to accept poor pay and bad treatment. The Kipande became a way to lock them into low-wage jobs by tying their movement to the permission of their employers. If you didn’t have your Kipande, you could be arrested. If an employer wrote a bad note on your card, it followed you everywhere—effectively blacklisting you.

A System of Silent Segregation

While it wasn’t called “apartheid” in Kenya, the Kipande worked on the same racial logic. White settlers moved freely without such restrictions, while African men were criminalized for simply existing in certain areas without their documents. It was impossible to find formal work without it, and nearly impossible to leave a bad employer if your Kipande record was tainted. In practice, it meant Africans could not live or work where they chose; their economic fate lay in the hands of a white settler or colonial officer.

Little-Known Facts About the Kipande

Few people know that the Kipande boxes were originally designed to hang from the neck to be visible at all times, much like a livestock tag. This humiliating feature caused outrage, and over time some men hid them under their shirts. The system was also one of the first in Africa to use fingerprinting for mass population control, decades before it became common in other colonies. It created one of the earliest large-scale fingerprint databases on the continent—information that gave the colonial government unprecedented surveillance power.

Resistance to the Kipande was constant but often quiet. Workers sabotaged the system by “losing” their Kipandes, swapping them, or giving false information. In the 1940s and 50s, as Kenya’s independence movement gathered strength, the Kipande became a symbol of colonial oppression—often mentioned in the same breath as forced labor, land alienation, and heavy taxation.

The End of the Kipande

The Kipande system officially ended in 1947, replaced by an identity card system that—while still restrictive—was less explicitly tied to labor control. But its legacy lived on. Many of the ideas behind it, from fingerprint tracking to strict movement passes, resurfaced in different forms during the Mau Mau Emergency in the 1950s.