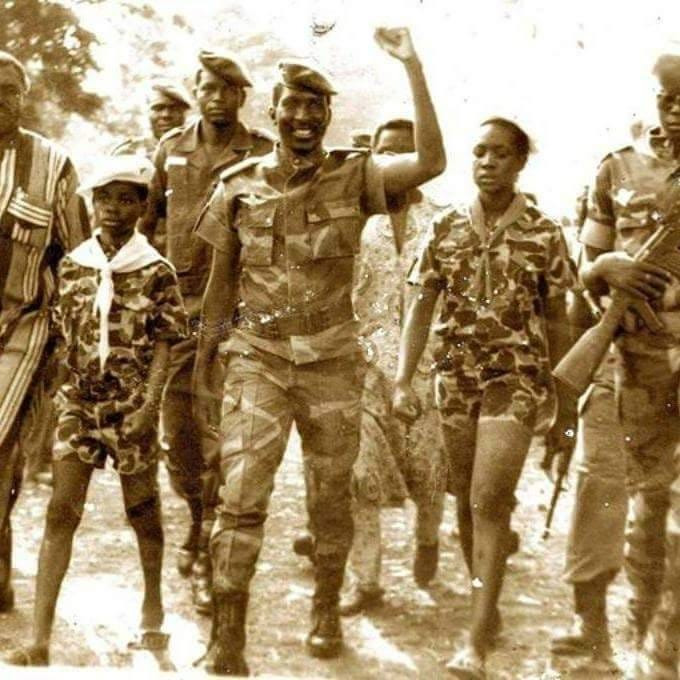

In the pantheon of African leaders, few shine as brightly—or as briefly—as Thomas Sankara, the revolutionary who transformed Burkina Faso in the 1980s. Nicknamed “Africa’s Che Guevara,” Sankara was more than a soldier in uniform. He was a visionary, a Pan-Africanist, and a reformer who dared to reimagine what an independent African nation could look like.

When Sankara seized power in 1983 at the age of 33, the country was still known as Upper Volta, a name inherited from French colonial rule. One of his first acts was renaming it Burkina Faso, which translates as “Land of Upright People.” This symbolic rebirth was Sankara’s way of telling the world—and Burkinabè citizens—that dignity, integrity, and pride were to define their nation.

His revolution was bold, radical, and fast-moving. Sankara embarked on campaigns that most African leaders of his time would not dare attempt. He launched one of the continent’s most ambitious reforestation projects, planting millions of trees to fight the expanding Sahara Desert. He spearheaded mass vaccination drives, dramatically reducing infant mortality. He made education a cornerstone of his revolution, building schools across the country and insisting that literacy was the foundation of freedom.

But Sankara’s revolution was not only about infrastructure and policy—it was about the spirit of independence. He rejected foreign aid, declaring that “he who feeds you, controls you.” Instead, he championed self-reliance, urging Burkinabè farmers to produce enough food to feed the nation. In just a few years, grain production rose significantly, moving the country toward food security.

A lesser-known truth about Sankara’s revolution lies in his radical approach to gender equality. In a society deeply rooted in patriarchal traditions, Sankara outlawed forced marriages, banned female genital mutilation, and encouraged women to take leadership roles in politics and the military. He insisted that no revolution could succeed without women’s liberation—a philosophy far ahead of its time in Africa.

Even his personal choices were revolutionary. He cut his own salary, sold off government luxury cars, and replaced them with modest Renault 5s. He refused to have his portrait displayed in public offices, urging citizens to hang up pictures of ordinary Burkinabè people instead. Sankara played the guitar, cycled to work, and mingled with villagers in a way that blurred the line between president and citizen.

Of course, his uncompromising style had consequences. Sankara’s fiery anti-imperialist speeches angered Western powers, while his rejection of aid unsettled elites both inside and outside the country. Political opponents accused him of being authoritarian, pointing to restrictions on dissent and the silencing of critics. By 1987, cracks were visible, and Sankara’s closest ally, Blaise Compaoré, orchestrated a coup that ended with Sankara’s assassination at just 37 years old.

What many don’t know is that Sankara seemed to anticipate this end. In one of his final speeches, he declared: “You can kill a revolutionary, but you cannot kill ideas.” These words became prophetic. Though his revolution was cut short, his vision of an independent Africa—free from neocolonialism, corruption, and exploitation—still inspires movements across the continent today.

Only wanna remark that you have a very decent site, I love the style and design it actually stands out.