Along the Kenyan coast, far from the tourist beaches and luxury resorts, lie sacred enclaves that tell a story older than colonial borders and national identity. These are the Kaya Forests of the Mijikenda, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of Africa’s most intriguing cultural landscapes. To most outsiders, they might appear as patches of thick vegetation, but to the Mijikenda people, they are living archives of history, spirituality, and resistance.

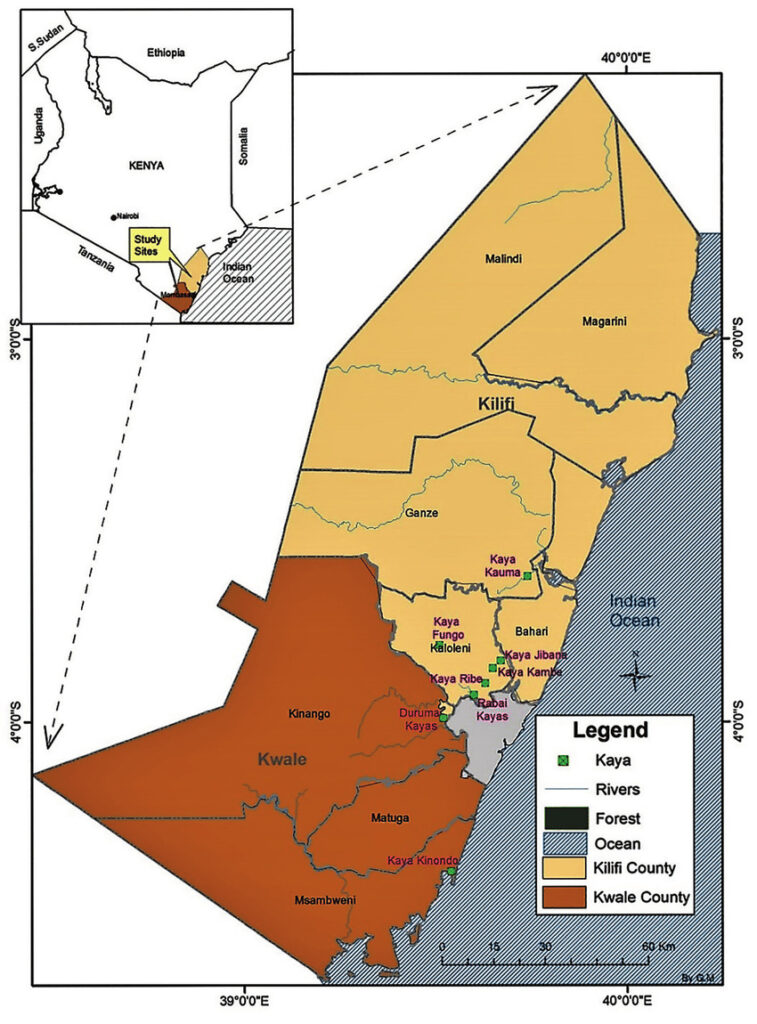

The Mijikenda, meaning “nine towns,” are a cluster of nine Bantu-speaking communities—such as the Giriama, Digo, Rabai, and Chonyi—who migrated to the Kenyan coast centuries ago. When they settled, they built fortified villages deep inside forests, known as Kayas. These were not just homes; they were fortresses against slave raiders, spiritual sanctuaries, and centers of governance.

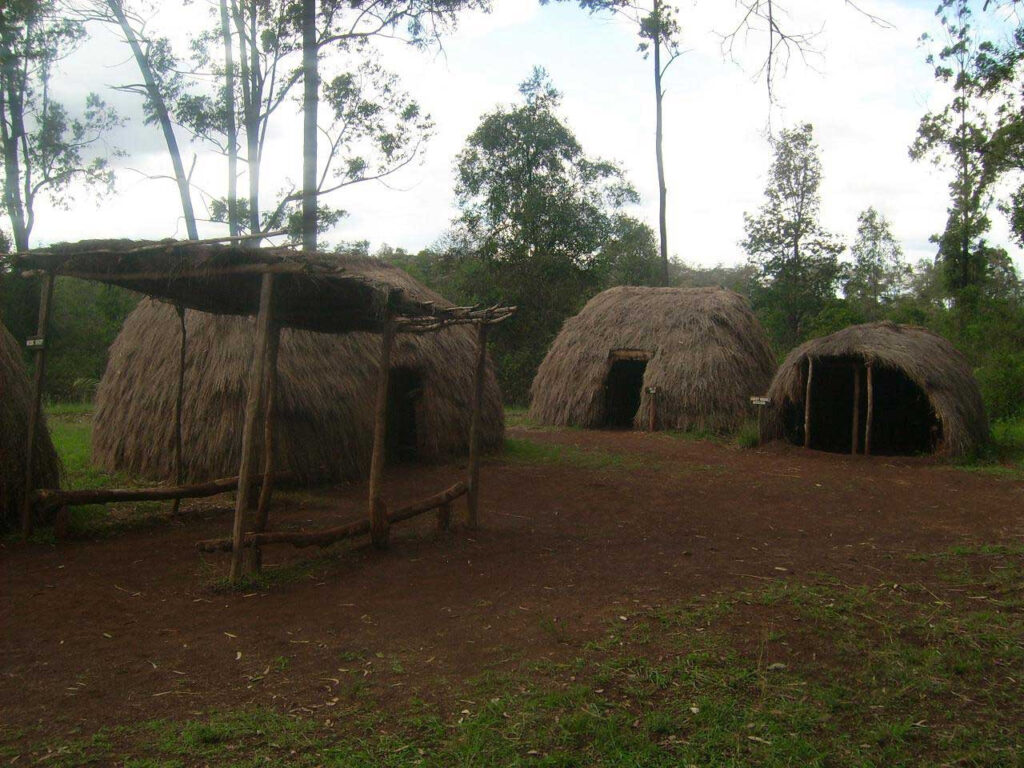

What makes the Kaya Forests fascinating is how they functioned as both physical and symbolic spaces. Hidden within dense trees, the villages were deliberately hard to access. This secrecy was essential during the 16th and 17th centuries when the East African coast was entangled in the slave trade and Portuguese-Arab conflicts. By retreating into the forests, the Mijikenda created safe havens where their culture could survive unbroken.

Yet, the importance of the Kayas went beyond defense. Each Kaya was governed by councils of elders who acted as spiritual guardians and custodians of communal law. Decisions on land, marriage, conflict, and even war were made within these sacred groves. The forests became the heart of social order, where rituals of initiation, prayers for rain, and offerings to ancestors were conducted. Some oral traditions suggest that the trees themselves were believed to carry ancestral spirits, making deforestation not just an ecological crime but a spiritual violation.

An often-overlooked fact is that the layout of a Kaya was highly symbolic. Houses were arranged in circles around a central meeting place, echoing the idea of unity and continuity. The paths leading into the forest were designed in ways that confused outsiders but guided insiders safely home. It was both architecture and psychology at work, centuries before formal urban planning.

Colonialism disrupted much of this. British administrators, failing to grasp the Kaya’s significance, dismissed them as “primitive villages.” Over time, people migrated out of the forests into open plains and towns. Still, the spiritual pull of the Kayas never faded. Today, even though few people live inside them, ceremonies and rituals continue, and elders still invoke them as sources of legitimacy.

Conservationists have also discovered that the Kaya Forests are biodiversity hotspots. Species of plants used in traditional medicine, rare birds, and even endangered animals thrive in these patches of forest that were protected long before modern conservation laws. In a way, the spiritual beliefs of the Mijikenda functioned as early environmental policies, ensuring balance between humans and nature.

Despite their UNESCO listing in 2008, the Kayas face threats from land encroachment, logging, and modernization. Yet, for the Mijikenda youth, rediscovering the Kayas has become a way to reclaim identity in a world that often erases indigenous heritage. The forests remind them that they descend from a people who resisted, adapted, and created systems of knowledge still relevant today.

Good day! This is kind of off topic but I need some guidance from an established blog. Is it very difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick. I’m thinking about making my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any points or suggestions? Appreciate it