When most people hear the words female pharaoh, Cleopatra instantly comes to mind. Her story, immortalized in plays, films, and history books, has overshadowed nearly every other woman who once ruled the Nile.

But ancient Egypt’s throne was no stranger to powerful queens who reigned in their own right. Their names may not roll off the tongue as easily as Cleopatra’s, yet their legacies are just as remarkable—and in some cases, even more groundbreaking.

One such figure is Sobekneferu, who ruled during the 12th Dynasty around 1800 BCE. She was the first woman to officially adopt the full royal titulary of a pharaoh, not just ruling as a queen regent but as a king in every ceremonial sense.

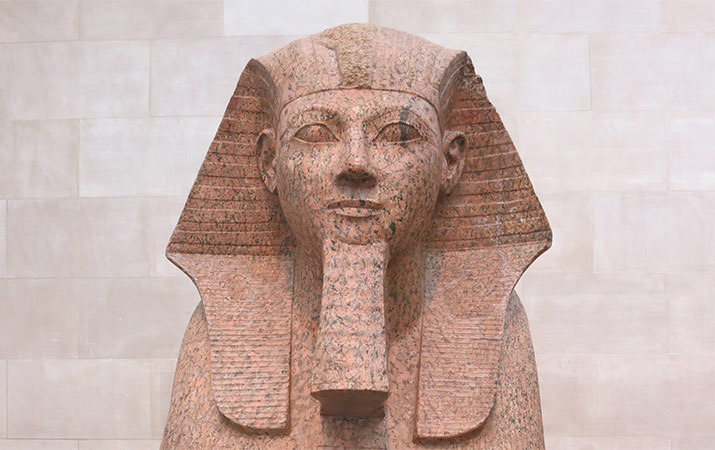

Statues of Sobekneferu show her blending feminine features with traditional male regalia, a visual compromise that reflected her unique position. Her reign, though short, stabilized Egypt at a critical moment and paved the way for future female rulers.

Centuries later came Hatshepsut, arguably the most successful female pharaoh in history. Ascending the throne in the 15th century BCE, she reigned for more than two decades, overseeing a period of prosperity and monumental building projects.

Her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari still stands as one of the most breathtaking architectural achievements of ancient Egypt. What’s less widely known is that Hatshepsut’s trade expeditions to Punt not only enriched Egypt but also introduced new plants and goods, some of which transformed Egyptian medicine and cuisine.

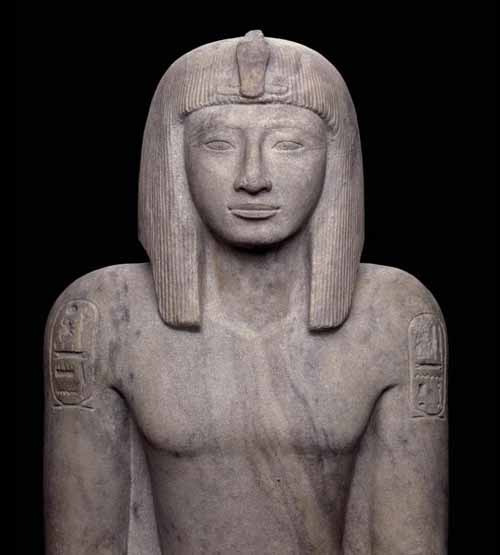

Another forgotten name is Twosret, the last ruler of the 19th Dynasty. Her reign was marked by political tension and intrigue, but archaeological evidence suggests she attempted to maintain stability during a turbulent era. Her tomb in the Valley of the Kings, unusually large for a female ruler, reflects both her ambition and her contested legacy.

There’s also Nefertiti, often remembered as the beautiful queen beside Akhenaten. But recent scholarship suggests she may have ruled as pharaoh after her husband’s death, possibly under the name Neferneferuaten. If true, this would place her not just as a supporting figure but as a ruler in her own right during one of Egypt’s most radical religious revolutions.

These women remind us that Cleopatra was not a one-off exception. Female leadership in Egypt was unusual but not unthinkable. The Egyptian belief in maat—cosmic order and balance—sometimes allowed women to rise when stability demanded it. Their reigns reveal a society far more flexible and pragmatic than the stereotypes of male-dominated antiquity often suggest.

Very efficiently written article. It will be helpful to anybody who usess it, as well as me. Keep doing what you are doing – looking forward to more posts.