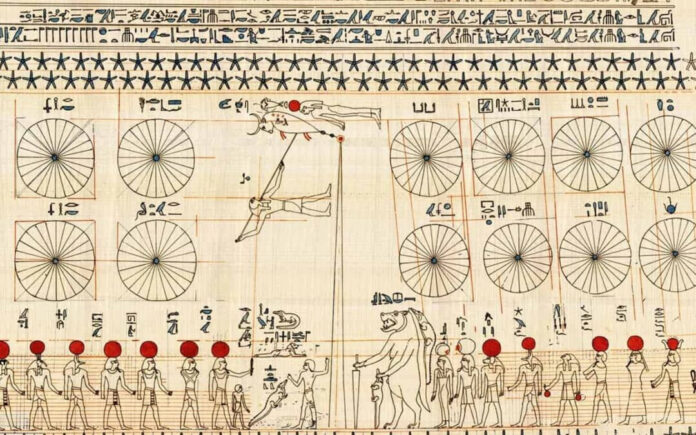

When most people think about calendars and mathematics, their minds jump to the Egyptians with their hieroglyphic records or to Greece with its geometric traditions. But across Africa, long before colonial contact, communities developed their own sophisticated ways of tracking time and solving numerical problems.

These traditional African calendars and mathematical systems were not just practical tools for farming or trade; they were deeply tied to culture, spirituality, and science.

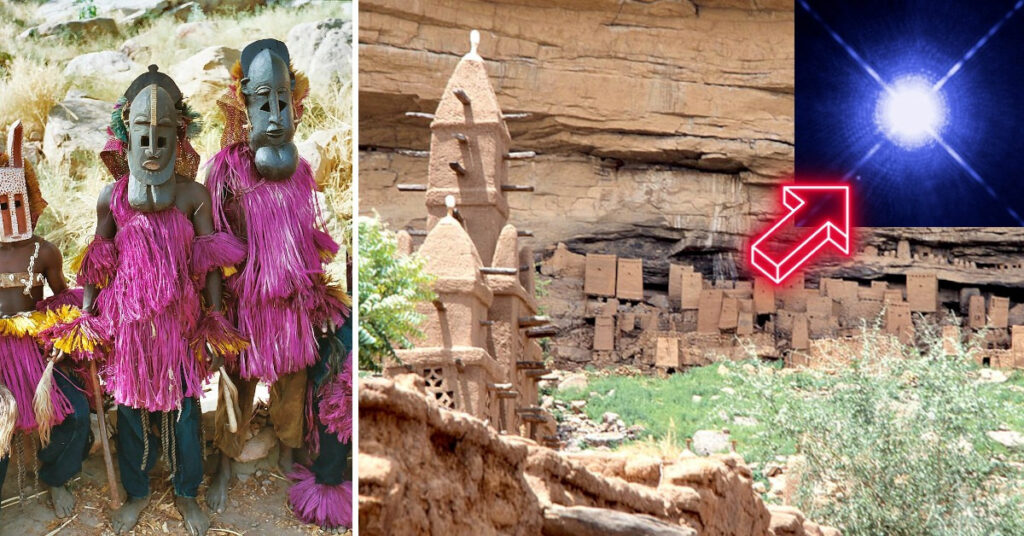

Take the Dogon people of Mali, for example. Their calendar was rooted in astronomy, with a focus on the cycles of Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Western astronomers only confirmed some of these details in the 20th century, yet Dogon oral traditions had carried the knowledge for centuries. The Dogon calendar split time into 60-year cycles, a system that feels strikingly modern given how complex it is to calculate.

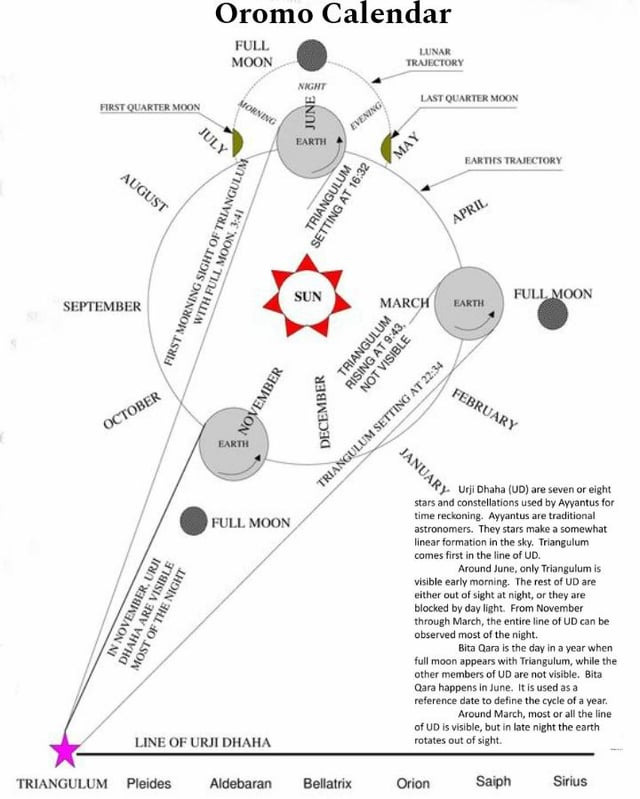

In East Africa, the Borana of Ethiopia used a lunar calendar that required keen astronomical observation. Twelve months were mapped out by tracking the moon’s position against specific stars, and every year, elders would gather to align the community’s activities—planting, rituals, and migrations—according to this celestial guide. It wasn’t a rough estimate of time; it was accurate enough to rival other ancient calendars across the world.

Mathematics, too, had a rich presence in African societies. The Ishango bone, discovered near the border of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, is one of the world’s oldest known mathematical artifacts, dating back over 20,000 years. Carved into its surface are patterns of notches that suggest knowledge of multiplication, division, and even prime numbers—long before such concepts were formalized elsewhere. Some researchers believe it also functioned as a lunar calendar, making it a dual tool of both math and timekeeping.

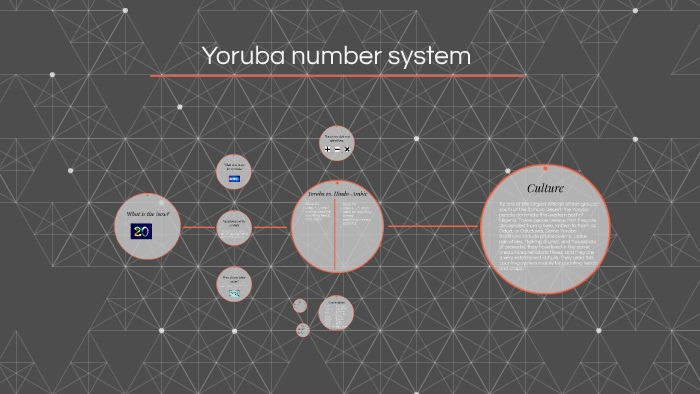

Further south, the Yoruba people of Nigeria developed a numerical system based on twenty, known as a vigesimal system. Instead of simply counting in tens, their structure combined subtraction and addition around multiples of twenty. For example, the number 45 would be described as “five less than fifty.” This wasn’t a quirky local choice; it showed a deep understanding of arithmetic logic, one that shaped trade, markets, and record-keeping in Yoruba society.

Even architecture reveals hidden mathematical genius. The Great Zimbabwe ruins are a perfect example. The massive stone enclosures were constructed with intricate geometric precision, yet no mortar was used to bind the stones. The builders relied on advanced spatial reasoning and proportional systems, skills that remain underappreciated in mainstream history.

Traditional African calendars and mathematical systems also carried spiritual meaning. Numbers were rarely neutral. Among the Akan of Ghana, for instance, the number seven held symbolic power, representing completeness and balance in rituals. Calendrical cycles weren’t just agricultural schedules; they were reminders of harmony between humans, nature, and the cosmos.

The tragedy is that many of these intellectual achievements were dismissed or erased under colonial rule. European scholars often labeled African societies as “oral” and “primitive,” ignoring the scientific sophistication embedded in their cultural practices. But today, more researchers are uncovering these systems, showing that Africa was never simply a receiver of foreign knowledge—it was a cradle of scientific thought in its own right.

By revisiting these traditional calendars and mathematical systems, we gain more than just historical curiosity. We see how African communities connected logic with spirituality, science with culture, and numbers with daily life. Their inventions remind us that time and mathematics are not just cold, universal truths—they are cultural expressions of how people understood and shaped their world.

In many ways, these ancient systems are still alive. Farmers in parts of Ethiopia still consult lunar calendars for planting. Yoruba counting methods influence language and commerce. The Ishango bone rests in a museum, silently reminding us that the story of numbers is not just Greek or Egyptian, but deeply African too.

Hello there! Quick question that’s totally off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My website looks weird when browsing from my iphone 4. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to fix this issue. If you have any recommendations, please share. Many thanks!