When you hear about the Luo of East Africa, you’ll often find their migration stories told with a mix of legend and memory. Like most African communities, the Luo didn’t leave behind stone inscriptions or detailed maps of their journeys. What they carried instead were myths, oral traditions, and songs that passed from one generation to the next. These stories are not only captivating but also reveal fragments of historical truth hidden in the poetry of folklore.

One of the most repeated myths is that the Luo people came from the “north,” guided by great leaders who could summon the waters of the Nile to open paths for their people. In some versions, chiefs were said to have supernatural powers, commanding fish to appear from the river whenever food was scarce. While these stories may sound mythical, historians trace them back to the Luo’s strong relationship with the Nile.

The Luo are part of the Nilotic peoples, and their migrations from Southern Sudan into Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania centuries ago are well-documented. The poetic idea of chiefs “summoning fish” likely comes from their real expertise in fishing and water navigation, which distinguished them from many neighboring groups.

Another legend claims that the Luo carried “stones of protection” on their journey—mystical objects that would glow at night and guide them across unfamiliar lands. Archaeologists studying migration routes along the Nile have actually found evidence of iron and copper objects traded and used by Nilotic groups. Could these glowing “stones” have been fire-lit iron tools mistaken for magical artifacts in the telling of oral tradition? It’s possible, showing how myth and fact often intermingle.

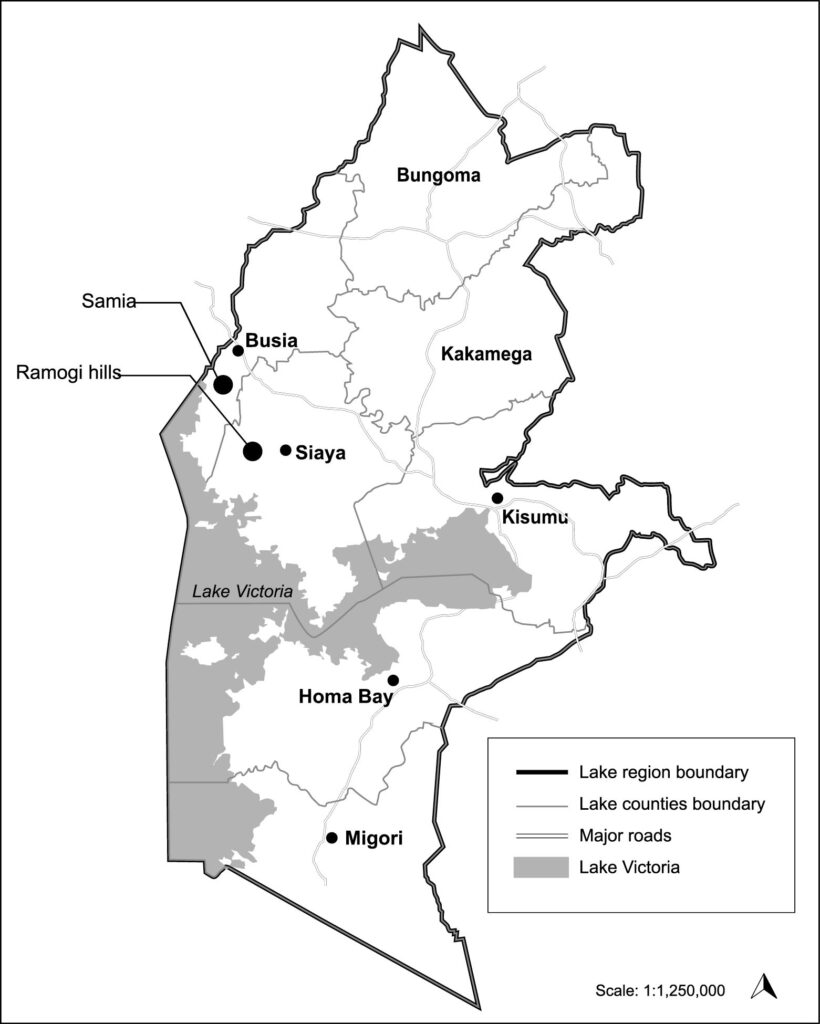

The Luo’s movement into present-day Kenya is remembered through stories of heroic ancestors like Ramogi Ajwang’, whose name is still revered. Oral traditions credit him with uniting clans, settling disputes, and teaching agricultural practices to complement fishing and cattle keeping. Historians suggest that “Ramogi” may not have been one single man but a title passed down among leaders, much like the way “Pharaoh” in Egypt was not one king but a dynastic title. This reshapes how we understand Luo heritage—not as a single dramatic migration led by one patriarch, but as waves of movement, settlement, and leadership over time.

Interestingly, the myths also record encounters with other communities, sometimes describing them as “giants” or “spirits of the land.” Scholars believe these accounts may refer to earlier Bantu and Cushitic-speaking groups who occupied parts of Kenya before the Luo arrival. The descriptions of giants could have been metaphors for people with different body builds, languages, or even war strategies that seemed unfamiliar and intimidating to the migrating Luo.

Today, the blending of myth and fact is more than just a historical curiosity. It’s part of the Luo identity, binding their past to their present. Myths gave meaning to their struggles and triumphs, while history provides evidence of their resilience, adaptability, and influence across East Africa. From the shores of Lake Victoria to the cultural heartlands of Kisumu, the echoes of these journeys still shape Luo music, politics, and traditions.

This page really has all of the information and facts I

needed concerning this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

I’m really glad you found the information helpful! That means a lot.

This website really has all of the information and facts I needed concerning this

subject and didn’t know who to ask.

I’m so glad the site gave you the answers you were looking for.Thanks for reading.

Wow, incredible blog layout! How long have you been blogging for?

you make blogging look easy. The overall look of your website is magnificent, let alone the content!

I’m gone to inform my little brother, that he should also pay a quick visit this weblog on regular basis to get updated from newest

news update.

That is a really good tip especially to those new to the blogosphere.

Short but very accurate info… Many thanks for sharing this one.

A must read post!

Awesome post.

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you

wrote the book in it or something. I think that you could do

with a few pics to drive the message home a bit, but other than that, this is great blog.

A great read. I will certainly be back.

Hi, all the time i used to check weblog posts here in the early hours in the morning,

as i enjoy to learn more and more.