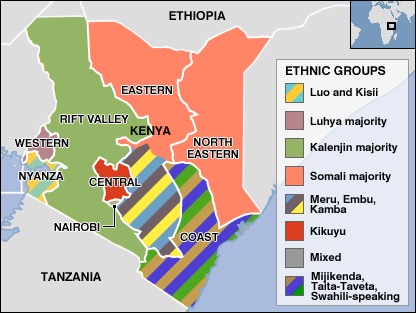

In the farthest corners of Kenya—by quiet lakes, in tucked-away forests, and on the edges of forgotten roads—some of the country’s oldest languages are barely hanging on. They live in whispers, in elderly voices, in prayers, songs, and names that rarely find their way into textbooks or radio broadcasts. Kenya, known for its cultural richness, is home to over 60 languages, but several are now at risk of disappearing altogether.

Take Yaaku, for instance. Few Kenyans even know it exists. Once spoken by a hunter-gatherer community in the Mukogodo Forest near Dol Dol in Laikipia County, the language was swallowed up by the more dominant Maasai culture over generations.

Most Yaaku speakers today are actually ethnic Maasai, who have reconnected with the language after decades of disuse. A revival movement has taken root, led by elders and local activists determined to teach the language to the young before it vanishes for good.

Then there’s El Molo—a language nearly as endangered as the tiny community that speaks it. The El Molo people live along the shores of Lake Turkana. For decades, intermarriage and assimilation into the Samburu and Turkana cultures have pushed the El Molo language to the margins. In fact, fluent speakers today are mostly elderly. Children in El Molo villages grow up speaking Samburu, Swahili, or even English, while their ancestral tongue fades into silence.

The case of Boni, or Aweer, is just as urgent. The Boni are a forest-dwelling community in Lamu and parts of Tana River. Traditionally hunters and gatherers, they’ve long had a quiet relationship with the forest and its language. But after decades of marginalization, deforestation, and increased pressure to assimilate, their language is now spoken by fewer than 300 people. Without written texts or strong institutional support, Boni is at risk of disappearing in a generation.

What’s common in all these stories is the pressure of dominant languages—especially Kiswahili and English. They’re useful for education, jobs, and national unity. But in many cases, their rise has come at the cost of local tongues that once defined entire identities. Add to that decades of colonial and post-colonial education policies that sidelined indigenous languages, and you begin to understand how fragile these linguistic roots have become.

Still, not all hope is lost. Across Kenya, small but passionate efforts are trying to breathe life back into these fading languages. In some communities, elders are recording folktales, prayers, and conversations to preserve the sound and structure of their native tongues. Teachers and linguists are creating dictionaries and even mobile apps to help younger generations learn what their grandparents spoke fluently.

Language is more than just a way of speaking. It’s memory. It holds the rhythm of songs sung at harvest, the tone of lullabies, the names of medicinal herbs, and the etiquette of greetings passed down over centuries. When a language dies, a whole world dies with it—one that we might never fully recover.