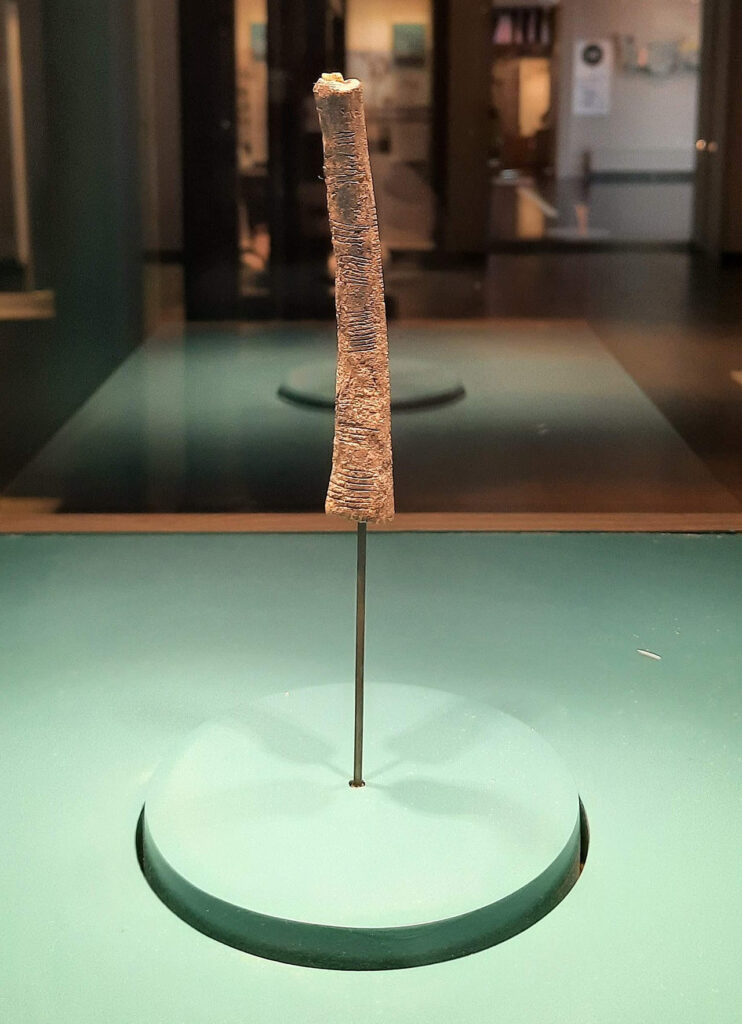

Imagine stumbling upon a pencil-sized tool, a simple piece of baboon bone etched with mysterious marks—yet it has the power to rewrite the history of math. That’s exactly what happened in the 1950s when Belgian geologist Jean de Heinzelin de Braucourt discovered the Ishango bone near Lake Edward in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This wasn’t an ordinary archaeological find. The Ishango bone, likely around 20,000 years old, is one of the earliest and clearest signs that our ancestors were working with numbers in a deliberate and organized way.

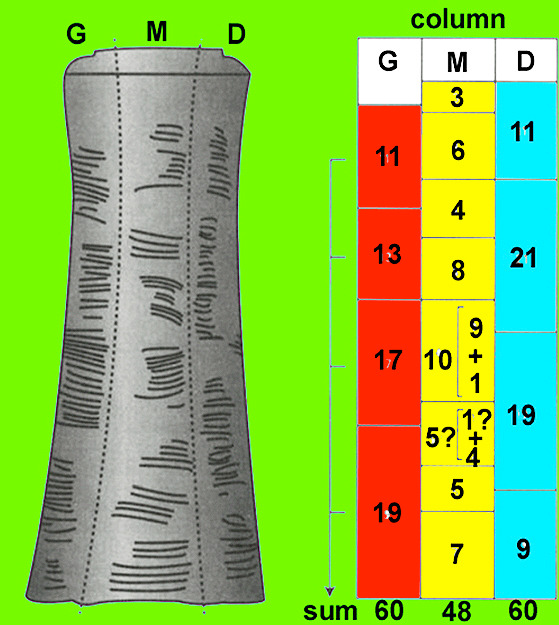

The tool is carved into three neat columns, each showing patterns of grouped notches. One column contains the numbers 19, 17, 13, and 11—four successive prime numbers between 10 and 20, adding up neatly to 60. That kind of precision suggests a deep understanding of numerical relationships. The neighboring column shows another sequence: 7 (or 8), 5, 5, 10, 8, 4, 6, 3—adding up to between 48 and 63. Scholars believe these markings hint at early arithmetic, including doubling, halving, or grouping.

Some researchers argue that the bone was more than just a tally stick. Mathematicians Dirk Huylebrouck and Vladimir Pletser suggested it could have been a primitive “slide rule,” built around a base-12 system with sub-bases of 3 and 4. In other words, it may have been a kind of ancient calculator.

Others see the Ishango bone as a lunar calendar. Harvard archaeologist Alexander Marshack examined the marks under a microscope and proposed that they correspond to lunar cycles—possibly a six-month calendar. He argued that the placement of the notches had positional meaning, not just symbolic value. Building on that idea, ethnomathematician Claudia Zaslavsky suggested a very personal possibility: perhaps the bone was created by a woman to track menstrual cycles in relation to the moon, tying mathematics directly to human life.

Still, caution remains. Scholars such as George Gheverghese Joseph remind us that one artifact, however intriguing, cannot prove everything. A second bone found at the site shows markings that do not fit neatly with these interpretations, leaving open the possibility of multiple uses and meanings.

More recently, new studies have found patterns that suggest cross-column symmetry, repeated sums, and intentional pairing. These discoveries point to the idea that the Ishango bone may have been designed with deeper layers of meaning, perhaps connected to myth, instruction, or even cosmic cycles.

Today, the Ishango bone is housed in Brussels at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, far from the African soil where it was once used. Its removal during the colonial era highlights an uncomfortable truth: many treasures of African heritage were taken and are still displayed far from their origins. There is now a growing call to return such artifacts so they can be celebrated in their rightful cultural context.

In the end, the Ishango bone is not just a relic. It is a whisper from humanity’s deep past, showing that early African communities were exploring mathematics and astronomy long before written history credited anyone else. Whether it was used as a calendar, an early calculator, or a record of prime numbers, the bone proves that Africa was—and remains—a cradle of knowledge, creativity, and scientific thought.

Superb blog! Do you have any hints for aspiring writers? I’m planning to start my own website soon but I’m a little lost on everything. Would you suggest starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a paid option? There are so many options out there that I’m totally confused .. Any ideas? Kudos!