What kind of African kingdom minted its own gold coins while Rome was still paying soldiers in stamped metal?

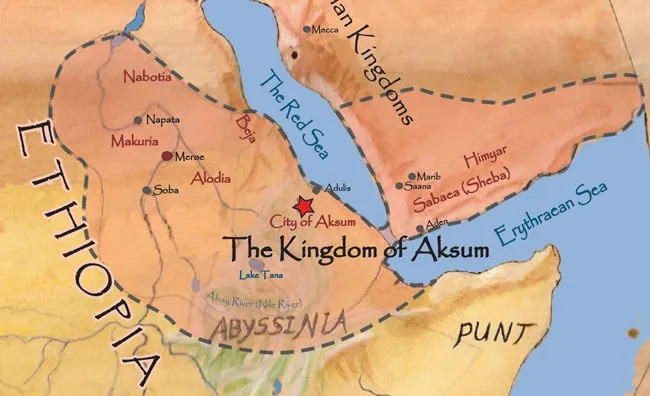

The answer sits in the highlands of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, where the Axum Empire rose into one of the most connected trade powers of the ancient world.

Axum did not grow rich by accident. Its capital stood near the Red Sea corridor, a maritime highway linking Africa, Arabia, India, and the Mediterranean. Every ship that crossed these waters carried more than goods. It carried influence, ideas, and wealth that Axum knew how to capture.

At the heart of Axum’s power was trade control. Ivory from the African interior, gold from Nubian and southern routes, rhinoceros horn, obsidian, salt, and enslaved labor passed through Axumite markets. In return came silk from India, wine and olive oil from the Roman world, and finely worked metals from Arabia. Axum was not just a stopover. It was a gatekeeper.

The empire’s port city of Adulis became one of the busiest harbors in the ancient world. Greek merchants, Arab sailors, and African traders met there under Axumite authority. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a first-century trade manual, lists Adulis as a major commercial hub, placing Axum firmly on the global trade map long before Europe’s rise.

Money tells a deeper story. Axum was one of the first African states to mint its own coins in gold, silver, and bronze. These coins carried royal portraits and inscriptions in Greek, signaling international confidence and literacy in global commerce. Trade partners trusted Axumite currency, a rare achievement outside Rome, Persia, and India.

Political strength followed economic power. Axumite kings projected authority across the Red Sea into southern Arabia, controlling trade chokepoints and protecting merchant routes. Military campaigns were not about conquest alone. They were about securing commerce.

Religion also traveled these routes. In the fourth century, King Ezana adopted Christianity, making Axum one of the earliest Christian states in the world. This was not a symbolic conversion. Christianity reshaped governance, law, and international alliances, especially with the Byzantine Empire. Axum became a religious bridge between Africa and the Mediterranean.

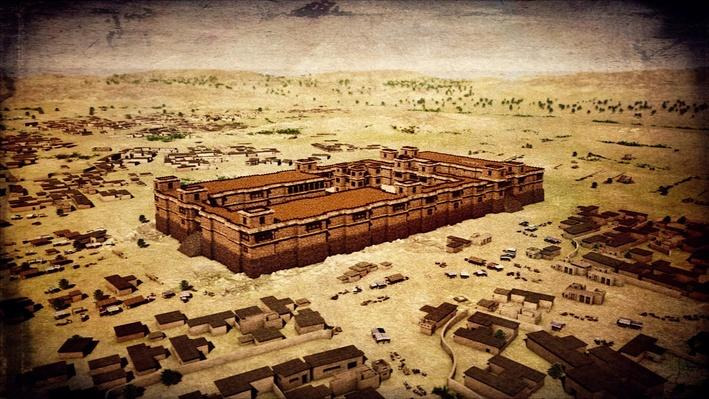

Axum’s monumental stone stelae still dominate its ancient capital. Carved from single blocks of granite, some rising over 20 meters high, these structures marked elite burials and royal authority. Their precision engineering speaks of skilled labor, organized leadership, and surplus wealth generated by trade.

Agriculture supported everything. Terraced farming in the highlands produced grain to feed cities, armies, and traders. Axum balanced foreign commerce with local food security, a key reason its power lasted for centuries.

Decline came quietly. Trade routes shifted after the rise of Islamic caliphates, redirecting Red Sea commerce. Environmental strain and political fragmentation weakened central control. Axum did not collapse overnight. It faded as global trade currents changed.

Yet Axum’s legacy remains visible. Ethiopia’s long Christian tradition, early literacy, and state formation trace back to this empire. More importantly, Axum challenges a false narrative. Africa was not waiting to be “discovered.” It was already trading, minting money, governing complex societies, and shaping world history.

Axum was not a footnote. It was a superpower built on ships, markets, and stone.