What does it mean when the family of a man who once banned Mau Mau memory now appears draped in its symbols, claiming closeness to a struggle he openly rejected?

That question sits at the heart of Kenya’s most uncomfortable historical debate. It forces us to look past slogans, ceremonies, and carefully staged reconciliations, and ask who truly fought colonial rule, who benefited from that fight, and who now controls its memory.

The Forest Fighters and the Absent Nationalist

Jomo Kenyatta did not fight in the forest. He never carried a rifle, never took the Mau Mau oath, and never lived the brutal life of the guerrilla camps. On that point, historians, veterans, and even Kenyatta’s own public record largely agree.

From the early 1950s onward, Kenyatta repeatedly distanced himself from Mau Mau, calling it a “disease” and later insisting it should be forgotten altogether. After independence, he banned the movement outright. That ban would survive his presidency and continue under Daniel arap Moi.

This creates an obvious tension. Mau Mau is widely understood as the armed struggle that forced Britain to accept Kenyan independence. Yet the man celebrated as the Father of the Nation spent much of his political life denying, suppressing, or minimizing that same struggle.

The two stories do not sit easily together.

Prison Turned Kenyatta Into a Symbol, Not a Fighter

When the Mau Mau uprising exploded in 1952, the British colonial government needed a familiar face to blame. Kenyatta was already internationally known, politically active, and deeply inconvenient.

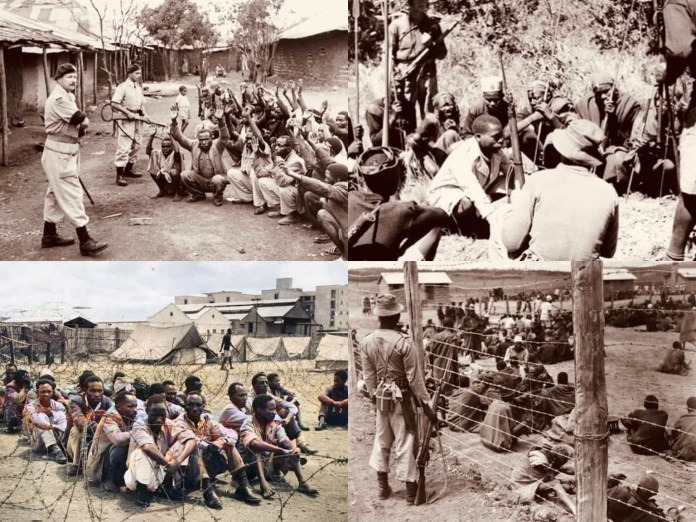

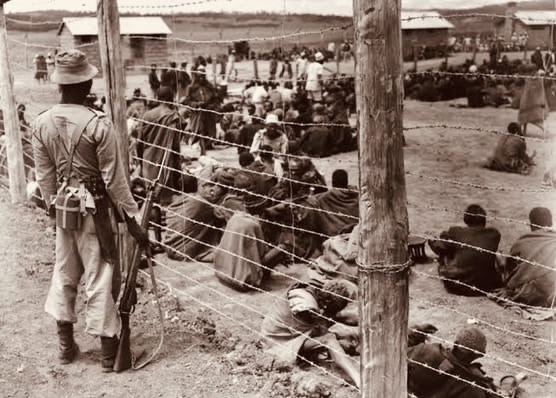

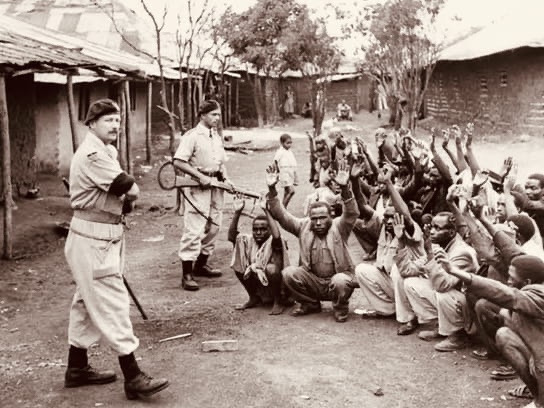

He was arrested, tried in a deeply flawed case, and locked away. The evidence against him was weak, but the political logic was strong. By removing Kenyatta, the British could present Mau Mau as criminal savagery rather than a political rebellion rooted in land theft and racial violence.

Ironically, that imprisonment elevated Kenyatta’s status. To many Kenyans suffering under Emergency rule, he became a symbol of African resistance, even as real fighters were being hunted, hanged, or buried in detention camps.

Kenyatta gained moral authority without sharing the physical cost of the war.

Mau Mau Was Not One Thing

Part of the confusion around Kenyatta’s legacy comes from a misunderstanding of Mau Mau itself.

Mau Mau was not a single organization with one leader and one strategy. It was a messy, fragmented resistance. Fighters in the forest, women supplying food, villagers coerced or committed, urban supporters, political sympathizers, and radical nationalists all played different roles.

Dedan Kimathi, the most iconic Mau Mau leader, did not see Kenyatta as a battlefield commander. He saw him as a political symbol. Kimathi fought with guns. Kenyatta fought with reputation and restraint.

That difference mattered. And it later hardened into resentment.

Silence as Strategy or Self-Preservation?

Kenyatta’s refusal to endorse Mau Mau violence remains the most controversial part of his story.

To fighters risking execution, his silence felt like abandonment. To Kenyatta, open support for armed rebellion would have guaranteed death and ended any chance of negotiating independence. The British were hanging fighters by the thousands. They were not preparing to hand power to revolutionaries.

This is where the moral argument sharpens. Was Kenyatta cautious, or was he calculating? Was he thinking of Kenya’s survival, or his own future?

History does not give a clean answer. It offers trade-offs that still sting.

Independence Without Justice for the Fighters

By the late 1950s, Mau Mau had been militarily crushed, but Britain had lost moral authority. Independence became inevitable, but it would be negotiated, not seized.

Kenyatta was released, rehabilitated, and positioned as the acceptable African leader. In 1963, he became prime minister, then president.

For Mau Mau veterans, independence brought bitterness. Land redistribution favored political elites and former settlers. Veterans were told not to expect rewards. Mau Mau remained banned. Radical voices were silenced.

For many fighters, this confirmed their worst fears. The man who benefited most from their sacrifice presided over a state that forgot them.

Was Kenyatta a British-Friendly Choice?

Critics argue that Kenyatta’s presidency protected colonial interests. Foreign capital was reassured. Colonial laws largely survived. Leftist opposition was crushed. Kenya avoided civil war, but it also avoided deep structural change.

Supporters counter that Kenyatta inherited a fragile country at risk of ethnic conflict and economic collapse. Pushing for radical redistribution could have shattered the state before it had fully formed.

Both arguments can be true at the same time.

Memory, Power, and the Kenyatta Name

This unresolved tension explains why recent attempts by the Kenyatta family to associate themselves with Mau Mau have been met with skepticism.

Ceremonies, symbolic gestures, and claims of forest friendships clash with decades of documented hostility toward Mau Mau memory. For veterans who were ignored, jailed, or dismissed after independence, such moments feel less like reconciliation and more like appropriation.

History is not just about what happened. It is about who gets to tell the story, and when.

A Nationalist, Not a Revolutionary

Jomo Kenyatta was not a revolutionary in the mold of Frantz Fanon or Thomas Sankara. He believed in order, hierarchy, and gradual change. Mau Mau was born from desperation, violence, and stolen land.

That ideological gap explains much of the bitterness. When independence came, Kenyatta chose the state over the struggle.

So, Betrayal or Long Game?

Did Jomo Kenyatta betray the Mau Mau?

He did not fight with them. He did not defend their methods. He did not reward them once in power. Those facts are hard to escape.

But he also endured imprisonment, became a symbol of resistance, and navigated a brutal colonial system that crushed open rebellion. Without him, Kenya might not have emerged intact, or at all.

Kenyatta was neither pure hero nor simple traitor. He was a political survivor making choices that protected a nation while wounding those who bled for it.

Kenya still lives inside that contradiction. Between order and justice. Between memory and power. Between the country Kenyatta built and the revolution Mau Mau imagined.

That unresolved tension is not a failure of history. It is its most honest legacy.