What if the most powerful pharaohs ever crowned in Egypt did not come from the Nile Delta but from deep in Nubia, south of Aswan?

In the eighth century BCE, the Kingdom of Kush did what no foreign power had managed before: it conquered Egypt, restored its ancient traditions, and ruled as legitimate pharaohs. These Kushite kings, often called the Black Pharaohs, governed an empire that stretched from modern-day Sudan to the Mediterranean, reshaping Egyptian history in ways many textbooks still gloss over.

The Kingdom of Kush was centered in Nubia, a region rich in gold, iron, and skilled warriors, giving it economic and military strength long before it marched north. By the time Egypt was fractured by internal rivalries and weakened dynasties, Kush was unified, disciplined, and deeply respectful of Egyptian religion and culture. This balance of power set the stage for one of Africa’s most remarkable imperial takeovers.

King Piye, also known as Piankhi, led the Kushite advance into Egypt not as a destroyer but as a reformer. His victory stela reveals a ruler more concerned with religious purity than conquest, scolding Egyptian leaders for neglecting the gods rather than celebrating military dominance. This approach won him legitimacy, allowing Kushite rulers to be accepted as true pharaohs rather than foreign occupiers.

Under the 25th Dynasty, Egypt experienced a cultural revival rooted in tradition. Kushite pharaohs restored neglected temples, revived pyramid building, and emphasized ancient religious practices that earlier dynasties had abandoned. Remarkably, they built their own pyramids in Nubia, smaller but steeper than those at Giza, creating the largest concentration of pyramids in Africa.

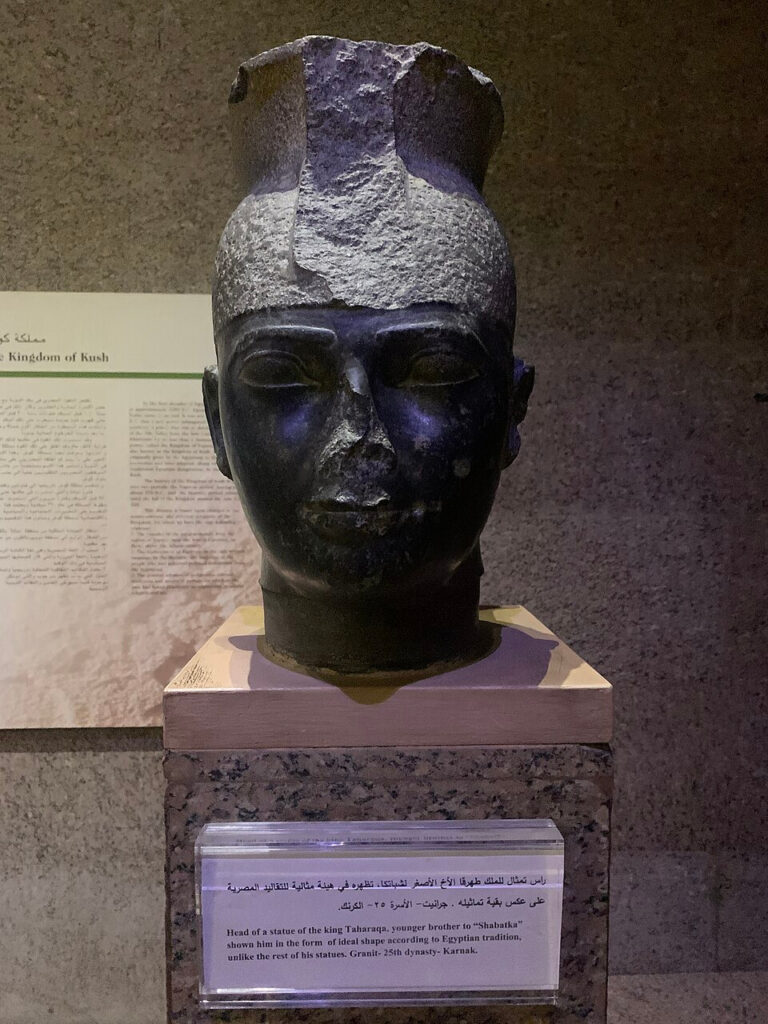

One little-known fact is that Kushite rulers deliberately styled themselves after Old Kingdom pharaohs from more than a thousand years earlier. Statues of Taharqa, one of the most powerful Kushite kings, show him wearing archaic regalia to signal continuity with Egypt’s golden past. This was political messaging carved in stone, designed to unite a divided land.

The reign of Taharqa marked the height of Kushite power, with Egypt once again acting as a major regional force. Biblical texts even reference his involvement in Near Eastern conflicts, highlighting how far Kushite influence reached. Yet this same visibility attracted a dangerous rival: the Assyrian Empire.

Assyrian invasions eventually pushed the Kushite pharaohs out of Egypt, but they did not collapse. Instead, the Kingdom of Kush retreated south and continued to thrive for centuries at Meroë, developing its own writing system and becoming a major iron-producing center. This survival challenges the idea that defeat in Egypt meant the end of Kushite civilization.

What makes the Kingdom of Kush especially significant is how clearly it disrupts outdated narratives about ancient Africa. These rulers were not imitators borrowing civilization from Egypt; they were Africans shaping one of the world’s greatest civilizations from positions of power and confidence. Their story proves that ancient Egypt was part of a broader African world, not isolated from it.

The Kingdom of Kush did not merely rule Egypt; it reminded Egypt of its own roots, leaving behind a chapter of history that deserves far more attention than it receives.