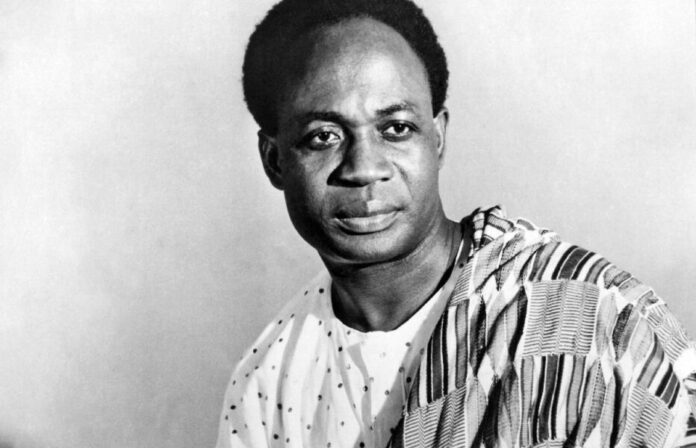

What kind of leader looks at a newly independent nation and sees an entire continent waiting to rise?

Kwame Nkrumah did exactly that, and his vision still challenges Africa today.

In 1957, as fireworks lit the night sky in Accra, Kwame Nkrumah was not celebrating Ghana alone; he was announcing a challenge to the entire African continent.

Nkrumah understood something many leaders avoided: political independence without unity would leave Africa vulnerable to new forms of control.

He saw colonial borders as administrative accidents, not sacred lines, and believed they would keep Africans divided long after colonial flags came down.

Born in Nkroful in 1909, Nkrumah’s early education exposed him to both African traditions and Western political thought.

His years in the United States and the United Kingdom sharpened his ideas, especially his belief that Black liberation anywhere was tied to African freedom everywhere.

Unlike many nationalist leaders who focused narrowly on their own countries, Nkrumah spoke openly about continental responsibility.

He argued that Ghana’s independence was “meaningless unless it was linked up with the total liberation of Africa,” a statement that unsettled colonial powers and cautious African elites alike.

As Ghana’s first prime minister and later president, Nkrumah used the state as a tool for Pan-African action.

He funded liberation movements, hosted exiled freedom fighters, and turned Accra into a meeting point for revolutionaries from Algeria to South Africa.

Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism was not emotional rhetoric; it was a structured political vision.

He pushed for a United States of Africa with a common defense system, a shared foreign policy, and coordinated economic planning.

At the heart of his thinking was economic control.

Nkrumah warned that political independence without economic sovereignty would trap Africa in what he later called neocolonialism, a system where former colonizers still dictated trade, resources, and development paths.

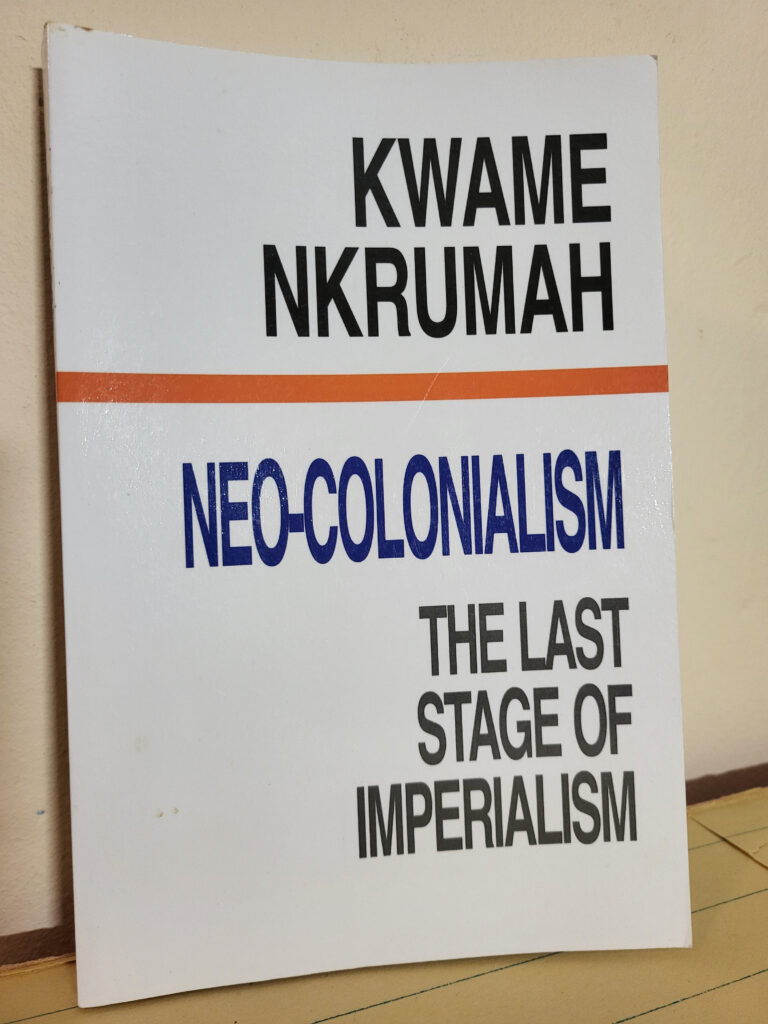

His book Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism exposed how foreign corporations, aid conditions, and military alliances could quietly replace direct rule.

The book was so threatening that it was banned in some Western countries and intensified efforts to isolate him diplomatically.

Nkrumah invested heavily in infrastructure and education because he believed ideas and industry were weapons of liberation.

Projects like the Akosombo Dam were designed not only to power Ghana but to fuel regional industrial growth.

Critics accused him of authoritarian tendencies, and some of the criticism was valid.

Yet even his political mistakes were rooted in a fear that internal division would derail Africa’s larger liberation project.

In 1966, while Nkrumah was on a peace mission to Vietnam, a military coup overthrew his government.

Many Africans later came to see the coup as confirmation of his warnings about foreign interference and internal betrayal.

Exiled but unbroken, Nkrumah continued writing and advising liberation movements until his death in 1972.

His ideas survived him, quietly shaping institutions like the Organization of African Unity and, later, the African Union.

Today, when Africans debate a common currency, open borders, or continental trade, they are revisiting Nkrumah’s unfinished work.

The African Continental Free Trade Area echoes his insistence that fragmented markets weaken African bargaining power.

Nkrumah’s relevance lies not in nostalgia but in urgency.

He forces Africa to confront an uncomfortable question: is the continent content with symbolic independence, or is it ready for real unity?